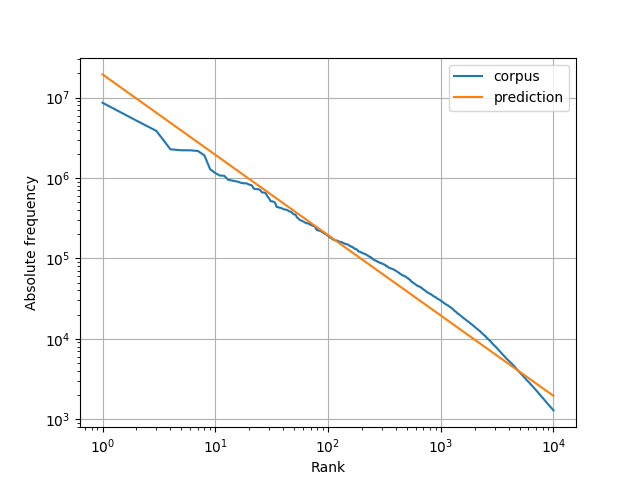

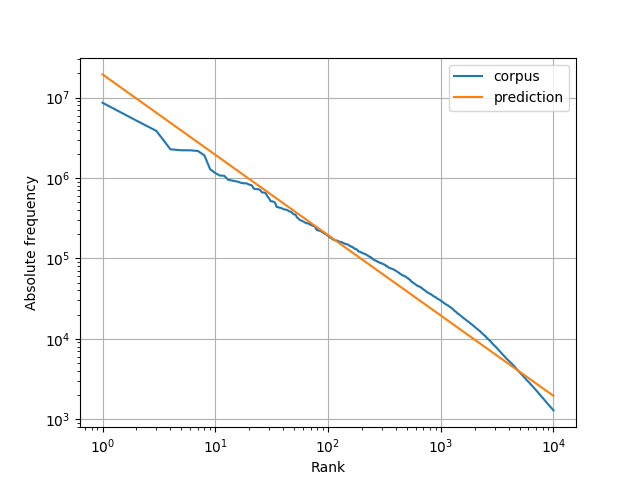

Fig. 1: Log-log plot of actual (blue) and predicted (orange) absolute lemma frequency against rank

That's a question I ask myself every time I painstakingly try to figure out at least the gist of an article from a Russian newspaper. To answer the question, I performed some lexical frequency analysis on a corpus of Russian news articles. As expected from Zipf's law, a relatively small number of different words makes up a large percentage of the whole corpus. Unfortunately, to understand at least 90% of all tokens, we still need to know around 7,000 different lexemes.

The data which all frequency counts in this post are based on are taken from the shared task on machine translation at the EMNLP 2015 Workshop on Statistical Machine Translation (Lisbon, Portugal). More specifically, I used the news crawl articles from 2014, a subset of the monolingual language model training data, consisting of more than 190 million tokens.

What is a word? When people talk about different 'words' in the context of natural language processing (NLP), they usually mean tokens (strings of characters delimited by white space and sometimes punctuation), or token types (distinct tokens). In the context of language learning, knowing a 'word' usually means knowing a lexeme, a unit of lexical meaning often represented by a lemma (aka canonical/citation/dictionary form, headword). Inflected forms of a lexeme are called word-forms.

Here is a brief example: For the (rather nonsensical) string "Peter walks, I walk, people walk" our tokenizer (which ignores punctuation) gives us the following list of six tokens: Peter, walks, I, walk, people, walk. Since walk appears twice, this list contains only five token types and five different word-forms1. Both walk and walks belong to the same lexeme, which is represented by the lemma walk (under which we could find it in a dictionary of English), so we have four different lexemes.

In a synthetic language like Russian, often a larger set of word-forms belongs to a single lexeme. Given some knowledge about Russian morphology, knowing the lemma in most cases is enough to understand all inflected forms. Thus instead of counting types, we should count lexemes or lemmas to get a good estimate of the number of words we need to know to read Russian news articles.

Tokenization and lemmatization is performed with Yandex MyStem via Denis Sukhonin's Python wrapper. Tokens containing non-word characters, digits or latin characters are excluded from the analysis. If MyStem does not find a lemma, we fall back to the token string (this happens for less than 0.4% of all tokens), so each token is assigned exactly one lemma.

For each lemma, we count the number of token occurences that are word-forms of the corresponding lexeme, the absolute frequency f. By sorting all lemmas in reverse order of their frequency, we can assign each of them a rank r and compute the cumulative percentage of all tokens belonging to lemmas of up to rank \(r\), the cumulative relative frequency \(cf_r\).

This is the result for the ten most frequent lemmas:

| Rank r | Lemma | Frequency f | cfr (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | в | 8,644,175 | 4.4 |

| 2 | и | 5,178,798 | 7.1 |

| 3 | на | 3,863,065 | 9.1 |

| 4 | не | 2,278,345 | 10.2 |

| 5 | что | 2,216,003 | 11.4 |

| 6 | с | 2,214,009 | 12.5 |

| 7 | быть | 2,170,487 | 13.6 |

| 8 | по | 1,916,732 | 14.6 |

| 9 | год | 1,288,221 | 15.3 |

| 10 | который | 1,153,170 | 15.9 |

We see that these ten lemmas alone cover almost 16% of all tokens in the corpus and that most of them are function words.

To get a better overview of the frequency distribution we can plot the absolute frequency of the 10,000 most frequent lemmas against their rank.

Fig. 1: Log-log plot of actual (blue) and predicted (orange) absolute lemma frequency against rank

The empirical relation between absolute frequency and rank in this log-log plot (blue) can be approximated2 by a straight line with negative slope (orange), which shows that frequency and rank are inversely proportional3. We have a few words with very high frequency and a long tail of words with low frequencies. This phenomenon is known as one of several incarnations of Zipf's law, which for word frequencies can be stated simply4 as $$ f(r) = Cr^{-1} $$

where \(r\) is the frequency rank, \(f(r)\) is the absolute frequency of the lemma with rank \(r\), and \(C\) is a constant of approximately 0.1 times the corpus size in tokens \(N_T\) (Zipf, 1949, ch. 2 III). Plotting this function with \(C=0.1 \cdot N_T\) for the first 10,000 ranks gives us the orange line in Fig. 1.

Based on Fig. 1 we can expect to cover a large share of tokens with only a small number of highly frequent lemmas.

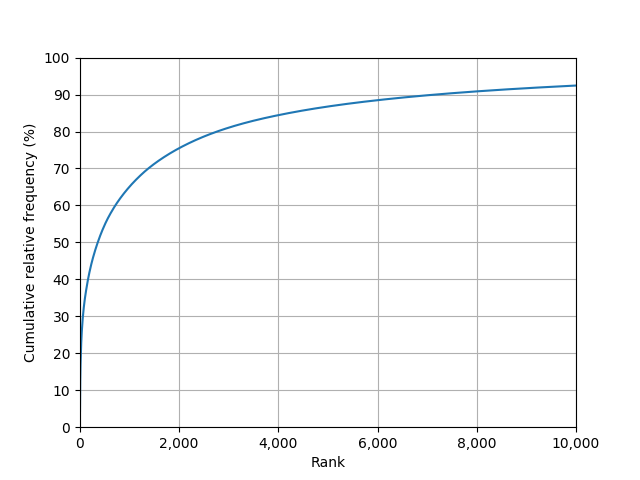

To see how our text understanding (or at least token coverage5) varies as a function of the number of most frequent words we know, let's have a look at the cumulative relative frequencies of the 10,000 most frequent lemmas:

Fig. 2: Cumulative relative token frequency against rank

If we know the 1,000 most frequent lemmas, we will be able to understand roughly 60% of all tokens we encounter in Russian news articles; with the 3,000 most frequent lemmas we cover over 80%. To read comfortably without frequent recourse to a dictionary, we probably need to know more than 90% of all tokens, that is, at least 7,000 lemmas.

Fig. 2 also shows why it's generally easier to make noticeable progress in the early stages of learning a language than in later stages. Knowing only a few more highly frequent words has huge effects on our text understanding, whereas adding a few more lesser frequent words has only little effect: The first 2,000 lemmas improve our text understanding by more than 75%, adding 2,000 lemmas to a vocabulary of 8,000 lemmas only yields around 2% improvement. Even worse, learning these later 2,000 lemmas is far more difficult, as the probability of encountering them again is low, hence they are not reinforced merely by reading random authentic texts.

So with 7,000 lexemes we can understand 90% of all newspaper texts. This number seems high - do we really need that many? There are several factors that make this a rather pessimistic estimate.

The lemmas used here are generated programmatically. As mentioned above, in less than 0.4% of all cases this didn't work at all. However, I didn't evaluate the quality of the generated lemmas -- from what I've seen they look good, but there could be a certain percentage of errors that artificially inflate their number. Additionally, any misspelling potentially creates a new 'false lemma'.

Some lexemes can be derived from others (or a common root) by regular morphological processes, e.g., inform > information, informative. If they share a core meaning, they maybe don’t need to be learned separately. Such related lexemes (with all their word-forms) make up word families. To get a more optimistic estimate of the necessary vocabulary size, we should count word families instead of lexemes. However, the semantic relations between such derivates can be opaque, either because their meaning is not fully compositional right from the beginning or because the morphological processes are not productive anymore and the lexical semantics of the derivates have developed in different directions. Thus we might not be able to correctly guess the meaning of one lexeme based on another from the same word family as the following English examples from Newmeyer (2009) show:

For our analysis we make the simplifying assumption that there is a one-to-one correspondence between tokens and lexemes. In reality, lexemes can consist of multiple tokens, e.g., San Francisco. More generally, we often learn collocations instead of single words.

Another point that should be addressed are names, e.g., of people, places, companies and brands. All of these are counted as ordinary lexemes in this analysis. But often articles introduce names to the reader, which means he or she doesn't need to know them in advance. Even if names aren't introduced explicitly, they usually stand out, information about their referents can be inferred, and not knowing them doesn't necessarily hinder comprehension.

Finally, the corpus used for this analysis is quite large and heterogeneous. People usually don't read random newspaper articles, instead they follow their interests—maybe they are interested in sports, politics, world news, or the latest developments at the stock market. The vocabulary of any of these sub-domains will be far more restricted, thus we can hope to read articles about our favorite topics knowing far less than 7,000 lexemes.

1 Note that the concept of token types comes from natural language processing and is not identical with the linguistic concept of word-forms. If our tokenizer would split on whitespace only, punctuation characters would be considered tokens, but not word-forms. Similarly, in the case of missing spaces, several adjacent word-forms may become one token.

2 Because frequency and rank are estimated on the same corpus, the empirical distribution might seem more regular than it actually is due to correlated errors (Piantadosi, 2014). However, for our purposes this error is negligible.

3 This relationship only appears linear in a log-log plot: \(\log(\frac{C}{r}) = - \log(r) + \log(C)\).

4 A more general version of this power law was proposed by Mandelbrot (1953): \(f(r) = C (r + a)^{-b}\) where \(a\) and \(b\) are constants (in our case \(a=0\) and \(b=1\)).

5 There seems to be a linear relationship between the percentage of known words and reading comprehension, but it's not the only factor, see Schmitt et al. (2011).

Mandelbrot, B. (1953). An informational theory of the statistical structure of language. Communication theory, 84, 486-502.

Newmeyer, F. (2009). Current challenges to the lexicalist hypothesis. Time and again: Theoretical perspectives on formal linguistics, 91-117.

Piantadosi, S. T. (2014). Zipf’s word frequency law in natural language: A critical review and future directions. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 21(5), 1112-1130.

Schmitt, N., Jiang, X., & Grabe, W. (2011). The percentage of words known in a text and reading comprehension. The Modern Language Journal, 95(1), 26-43.

Zipf, G. K. (1949). Human behavior and the principle of least effort: An introduction to human ecology. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

This page was moved from my old website.